I have been hesitant to fully explain the beginning of my persistent pain journey. Any re-telling of my story will inevitably be one-sided as I do not know the view of my clinicians, either at the relevant time or now. I am reliant on my memory of events, which go back to times when I was in a great deal of pain and fundamentally quite ill and distressed.

However, I now wonder if telling my version of some of the difficulties that I encountered at the beginning of my journey might help some to further realise the importance of more person centred, evidence based, healthcare. My hope is that this might help other patients to experience better, more personalised, healthcare.

The start of my persistent pain journey

Eleven years ago, following a two-week period of unusually heavy lifting, I entered the world of persistent pain. My story started on a Saturday morning. At first, I could feel my right leg starting to hurt. It was annoying, but nothing too bad. However, by lunch time I found myself in a great deal of pain. By early afternoon I was experiencing severe pain in both my back and legs, and I could barely walk. The pain progressed quickly.

The severe pain continued the next day, and my husband called out a GP. Armed with strong painkillers I assumed that things would settle, however Monday morning saw no improvement, and if anything, the pain was worse. I was almost totally unable to walk. I phoned 101 for advice, and they called out an ambulance.

This was the start of my Evidence Based Practice healthcare, which for a number of years proved narrow and largely ineffective for me.

My hospital admittance

I was admitted to hospital largely because I had been unable to go to the toilet for over twenty-four hours. The back and leg pain that I was experiencing was beyond anything I’d experienced before. I was transported to accident and emergency by ambulance and left in a curtained cubicle.

Shortly after arriving a nurse came in and said she was going to insert a catheter. To be honest this wasn’t a procedure that I really wanted, who would, and so I politely asked if it was really needed. I asked if I could understand and discuss the decision first. I will always remember the reaction of the nurse as I was made to feel, probably inadvertently, that I shouldn’t be asking and should just be doing what I was told. That was my first realisation that my thoughts and feelings were not of primary importance. I felt I was there ‘to be treated’.

Other memories I have of the admission process include being given a variety of medications to take, without really being told what they were for or being given any explanation of potential side effects. They were handed to me and I was expected to take them. Perhaps you could say that this was understandable on a busy accident and emergency unit, but I also don’t remember anyone sitting with me to explain the medications, their management, and their possible side effects during the following five days I stayed on the ward. There was plenty of time to do so.

I do remember someone on the ward, presumably a nurse, telling me that it was up to me whether I took a tablet for constipation or not, but I also remember this was not done in a particularly pleasant or helpful way. Her manner was dismissive. The other medications I was just given and expected to take. In some ways it is hard to criticise these actions, as I clearly needed very strong pain medication, but in my view those explanations and involvement of my thoughts in the medication decisions could, and should, have occurred. I should have been a partner in my care.

I now understand about Cauda Equina Syndrome, but of course I didn’t at the time. Cauda Equina Syndrome is a rare disorder that is usually a surgical emergency. Without very fast treatment you could be left with lasting damage, including incontinence and permanent paralysis of the legs. Its symptoms include severe low back pain, difficulty going to the toilet and pain and numbness in your leg. I had all these symptoms and so Cauda Equina Syndrome must have been of primary concern, but I don’t remember Cauda Equina Syndrome ever being discussed with me. I don’t remember being told what danger signs to look out for and report.

Shortly before being admitted to the ward I was asked by a doctor if I agreed with him that there was no need to do an MRI at that time, and it could be done the following day. I knew nothing about the dangers of Cauda Equina Syndrome. Indeed, I knew nothing about Cauda Equina Syndrome. I was not told that delaying an MRI could potentially have life-long repercussions for me. I had already been in hospital for around 9 hours without an MRI. Reflecting on my presentation at the time I’m now surprised an MRI hadn’t been done already.

I agreed with the doctor that waiting until the next day for an MRI was fine. Why wouldn’t I? I was merely being asked if I agreed, if it was ok. I wasn’t being given any facts or information that might help inform my decision making. Was this really shared decision making?

On the ward

The next day I met the consultant who had been put in charge of me on the ward. He was a consultant orthopaedic and spinal surgeon. It was a brief meeting in which he basically ordered an MRI, which I duly had later that day. It was well over 24 hours from admittance before I had an MRI and looking back that seems a long time to wait taken the symptoms I presented with that could have been suggestive of Cauda Equina Syndrome.

I remained on the ward for the next few days. I remained in excruciating pain, and barely able to walk or sit down. My bladder function remained impaired, but a little better than on admission. I was on high levels of pain medication, and so I was in a little less pain than when I entered hospital, but I was still in a great deal of difficulty. I worked hard every day to try and walk a bit further than the day before. I don’t remember receiving help with this. My part of the ward was close to the ward desk, and I could see nurses, doctors and therapists chatting to each other, but they rarely came to talk to me. I was largely ignored.

Discharge

Five days after entering hospital, on a Friday, I managed to walk to the day room, which was close to my section of the ward. Unbeknown to me a hospital doctor came to see me on his ward round whilst I was there. He was not a spinal specialist. Instead of being told that the doctor was on the ward and asked to return to my bed, or the doctor coming to the day room to talk with me, he decided to make decisions about me without either examining me, observing me, or talking with me.

After he had left the ward, I was told by a member of ward staff that the doctor had looked at my MRI results and decided to discharge me. I was offered the opportunity to stay in over the weekend if I wanted to in order to have an epidural injection some time the following week. At that time, I had absolutely no idea why I would want an epidural injection. My only knowledge and experience of epidurals was for childbirth! The ward staff were unable to tell me why I might want an epidural, and I was left not knowing what to do. I was due to go on holiday to Portugal the following week, and I asked the junior doctor if he thought I would be recovered enough to go. He said I probably would be.

Little did I realise what difficulty I was really in!

I made the decision, which I quickly regretted, to accept the discharge and go home.

Even now I cannot escape my persistent, albeit occasional, thoughts of ‘blame’ towards the hospital doctor who felt it was ok to make decisions about me, without even seeing me. I blame him for the confusion and chaos in my ensuing healthcare. I have often wondered if he had seen me and talked with me on the ward, as I strongly believe he should have, if my healthcare journey might have taken a different course. I often wonder if just perhaps I would have had a better chance of recovery. I will never know.

What I do know is that one act of a hospital doctor making decisions, without involving me as the patient in any way, caused me much ensuing confusion, distress and difficulty. I can’t know if it ‘caused’ me any ensuing physical harm, but that is something I will always wonder.

I now understand, but didn’t at the time, that my MRI results were almost certainly the reason I was discharged. It was many years later when I asked to see my GP medical notes that I first saw my MRI report. According to the radiologist, the MRI showed a disc prolapse with displacement of the right S1 nerve root within the canal. He said there was no nerve root compression. But was he right?

I would like to think that if the doctor had actually seen me, and discussed the results with me, that he would have noticed a disparity between those MRI results and the pain and distress I was in. I would like to think he might have thought a little bit harder about my ongoing healthcare. My narrative and my presentation were seemingly ignored.

I assume, but don’t know, that the doctor didn’t view the MRI himself, but only looked at the radiologist report. Six weeks later in outpatients, a rheumatologist shared my MRI scan with me and put forward a different opinion to that of the radiologist. He told me that I did have nerve root compression, and that a small part of the disc had broken off and was ‘floating’. The radiologist report was wrong!

I don’t know whether if the doctor had viewed my actual MRI at the time it would have made any difference to my discharge and healthcare, but perhaps at the very least a discussion could have taken place with me so that I could have better understood what my condition was, and what I should do. I was discharged with little idea.

I was discharged not knowing what would happen with follow-up, not knowing what to do if I didn’t recover sufficiently, not knowing about the danger signs of Cauda Equina Syndrome, not knowing what my condition actually was and not knowing what I should do going forward. The junior doctor that was left to explain my discharge to me was unable to tell me anything particularly helpful.

I was effectively ‘cast adrift’ not knowing where to turn.

After discharge

It didn’t take long for me to discover that I was in much more difficulty than I had perhaps realised. The pain I was suffering remained excruciating. I could barely walk, was unable to sit down, couldn’t dress myself, was unable to stand long enough to shower, and totally unable to get into a bath. My leg and foot felt numb and my bladder and bowel difficulties continued. The medications weren’t helping sufficiently, and I was in a great deal of distress. Three days after discharge I was so desperate that I went back to accident and emergency for help. Unfortunately, there was nothing much they could do. They didn’t feel able to re-admit me.

I was referred for immediate outpatient physiotherapy care. The physiotherapist appeared not to know what to do with me as my levels of pain and difficulty were so high. She gave me some generalised ergonomic advice and performed some manual therapy. I was given some very simple routine home exercises and after a relatively short time she discharged me to wait for an epidural.

I sought help from my GP surgery. I hadn’t seen a GP for the previous five years, perhaps more, and so I had no ‘relationship’ with a GP. It took a few months to build an effective relationship with just one GP. Once I had she worked hard to support me.

I found it difficult to recover from being discharged from hospital by the doctor with no discussion. I was in a great deal of pain, distress and difficulty. I didn’t know where to turn. Perhaps mistakenly I believed that if I could get back to talk with the spinal consultant who ordered my MRI, I would start to get some help. I couldn’t get back to see him through the NHS and so I asked my GP to refer me to him privately.

Two and a half weeks after discharge, my husband drove me the 30 miles I needed to travel to see him. I still couldn’t sit and so we had to risk laying the passenger seat back nearly flat and for me to travel that way. I can still remember the dreadful pain I experienced on that journey. Once there I couldn’t sit in the waiting room and had to be allowed to lie down in an empty consulting room. I remained in a bad way!

I remember the consultant being pleasant with me. He said he had no memory of seeing me on the ward, and no memory of ordering the MRI in hospital, but I recognized him, and I know he did. As I was seeing him privately, he didn’t have access to my MRI. He explained a little anatomy to me and suggested he make an NHS referral to a different local hospital for a lumbar epidural.

Around this time, I received a date for an outpatient appointment to see a rheumatologist at the original hospital. This was a surprise as apart from physiotherapy I hadn’t been told about follow up with a rheumatologist. I had no idea why I would be being seen by a rheumatologist, I knew I didn’t have rheumatoid arthritis. The appointment was arranged for around six weeks after my original injury. I now found myself under the care of two hospitals, with neither talking to each other, no sharing of information and no co-ordination of my healthcare. This splitting of my healthcare across the two hospitals, following two different pathways, caused further chaos and confusion.

Conservative care

For the first seventeen months of my journey I was treated ‘conservatively’. I understand this means I was treated with interventions such as injections, physiotherapy and medications instead of surgery. I understand that conservative treatment is often tried first in the hope that patients will sufficiently recover, without the need for surgery.

I still don’t understand why my healthcare professionals took such a long time before they decided that conservative treatment wasn’t working sufficiently for me. Seventeen months is a long time to wait for surgery. In my view if surgery was correctly indicated, which I believe it was, then it should have been discussed with me and decided upon many, many months before.

Throughout these seventeen months before surgery I was trying to continue to work, even though I was often taking strong opioids including morphine and in a great deal of distress. I remained in severe pain and my numbness and bladder and bowel problems continued. It was fifteen months before I saw a spinal surgeon, and seventeen months before I had surgery. Meanwhile my nerve root remained compressed, and I was suffering.

I now know, following a request to see my GP notes some years ago, that the rheumatologist I saw 6 weeks post injury told my GP that I ‘may yet come to surgery’. He didn’t say this to me, and he didn’t arrange any review or follow up with me. He didn’t copy me into his letter to my GP. I had no idea that surgery might be being considered.

I will never understand why the rheumatologist didn’t tell me he thought I might need surgery. I think it would have helped. If I had known that surgery was a potential option, perhaps I would have pushed to see him for a review. At the very least I might have discussed this with my GP. I wonder who the rheumatologist thought was going to review whether conservative care was working well enough for me.

I have often wondered whether if this rheumatologist had informed me of his thoughts, or had booked an appointment with me for review, my healthcare journey might have taken a different course, and if my permanent nerve damage and persistent pain could have been less. I will never know.

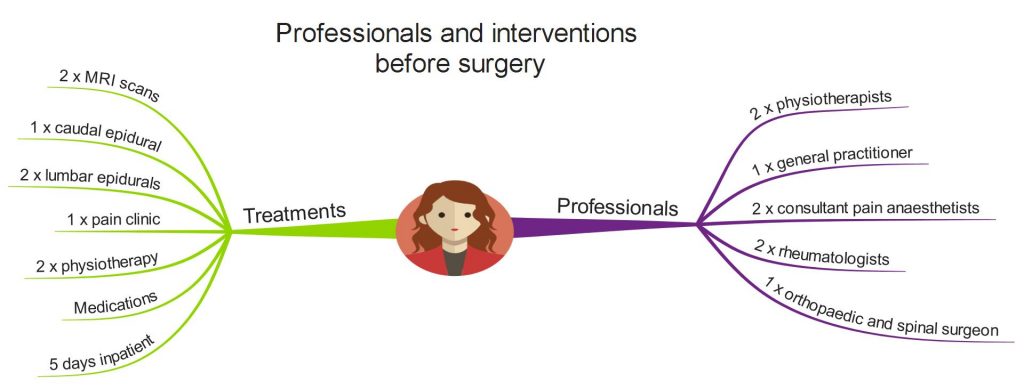

My coordination of care

My ‘conservative’ care involved a range of interventions, carried out by a range of professionals, none of which proved effective enough for me. These are the interventions and the professionals involved in my pre-surgery care.

My physiotherapy care mainly involved core exercises, which were largely ineffective for me. I also received some manual therapy. I was being given large quantities of strong opioids and other drugs, but these were not sufficiently effective for me, and caused a variety of severe side effects. Although I was seen in a pain clinic, this was only as part of the decision making process to have a lumbar epidural. I received no multi-disciplinary pain care.

I have sometimes wondered who in this myriad of professionals was responsible for monitoring and reviewing my conservative care? Were these professionals sharing information, apart from just back to my GP? Were they even doing that? Who was responsible for ensuring I was receiving effective, personalised care?

Could a lack of coordination of my care, lack of monitoring of my care and lack of sharing of information be the main reasons I waited seventeen months for surgery? Rather than because the seventeen months wait was clinically indicated in my case? Why wasn’t my care coordinated and monitored? Why was I being treated in ‘silos’? Why was I so long on conservative care?

Back surgery

My back surgery took place around seventeen months post injury. I had microdiscectomy and decompression surgery, which was undertaken in another hospital. There were four hospitals now involved in my care. Information sharing between them was poor.

Permanent nerve damage

I was told by my surgeons that my back surgery was technically successful. Unfortunately, I continued to experience pain and numbness.

I was told that my neuropathic and back pain was likely permanent, that my nerve root wouldn’t recover. They were right, my more recent MRIs show a nerve root that is visibly shrunken and tethered to the disc, and I continue to live in daily pain.

My emotions were strong. I grieved for the life I’d lost, and was fearful for my future. I couldn’t imagine how I could live with pain for the rest of my life.

I realise there is a chance my nerve root was immediately and permanently damaged when my disc prolapsed, but I believe there is a greater chance it was damaged through compression whilst being treated ‘conservatively’ for the seventeen months before surgery.

I will never know when my permanent nerve root damage occurred. It was probably a gradual process. I will always wonder whether if my surgery had happened earlier, the permanent nerve damage and resultant pain I now live with could have been less.

More of the same

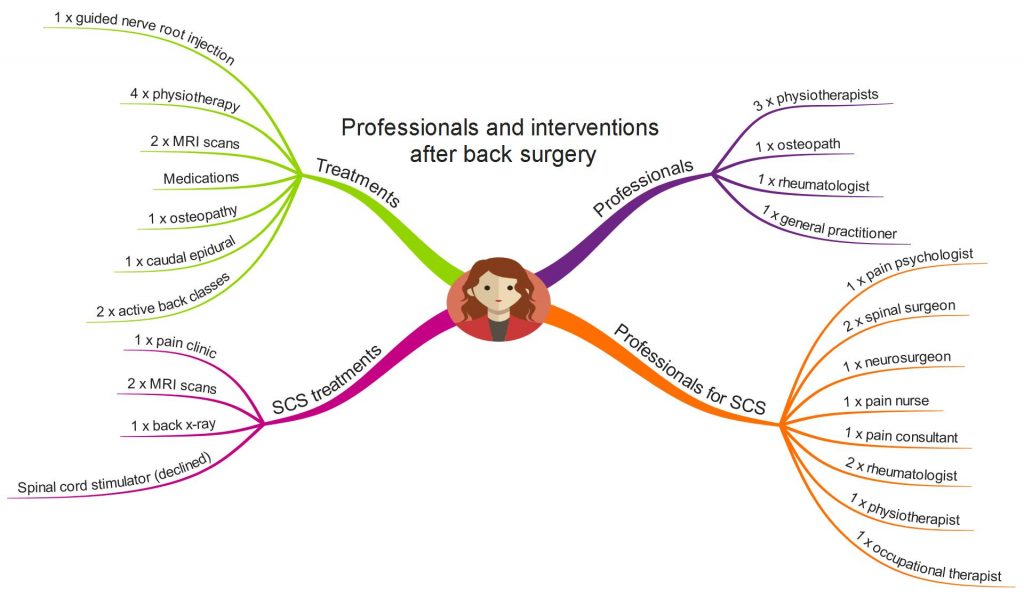

Following surgery, I continued with a range of interventions from a range of professionals, shown here.

My physiotherapy/osteopathy care involved some manual therapy and some basic exercise treatment. I continued taking pain medications including strong opioids, although by this time I was becoming more and more sensitive to medications and incurring increased side effects.

Some of the interventions and professionals marked on the MindMap relate to being placed on a Spinal Cord Stimulator (SCS) pathway. After two tortuous years on the SCS pathway, I eventually declined the option of a Spinal Cord Stimulator.

Although I was seen in the pain clinic, it was only as part of the spinal cord stimulator pathway decision making process. I did not receive multi-disciplinary pain clinic care.

The first four years of therapy care

Prior to surgery I had received two episodes of physiotherapy care. In the year following surgery I received two further episodes of therapy care, one from a physiotherapist, and one from an osteopath.

All four of these episodes of therapy care held similarities. They all resulted in what I would call ‘routine’ treatment. They were all very similar in nature. I think most of these episodes of care involved teaching me some simple anatomy, most involved some manual therapy, most involved a home exercise programme, most involved medication advice and one involved generalised ergonomic advice.

I wasn’t given much, if any, help to improve my day-to-day physical function and I wasn’t taught pain self-management. I wasn’t helped to walk again or to sit. My ‘lop-sideness’, and the maladaptive way I was holding and using my body, was ignored. Despite my pain being predominantly neuropathic, I wasn’t taught much, if anything, about neuropathic pain. Nobody taught me about the complexity of pain.

I expect most of these episodes of therapy care had some short-term benefits for me, but I don’t think they had any long term-benefits. I don’t think they improved my day-to-day physical function. I don’t look back and reflect on what I was taught in these therapy sessions, or apply any learning to my everyday life.

In my view these episodes of therapy care were ‘routine’ and weren’t sufficiently person-centred for me. The approaches used may have worked well for others, but overall they didn’t work well enough for me.

My life-changing physiotherapy care

I was trying to continue to work and get on with living my life, but there remained huge obstacles and difficulties for me. I remained in constant, and often severe, pain. Emotionally and physically I was struggling to cope with my situation. I was no longer able to tolerate opioid medications. None of the medical interventions I had received thus far were effective enough for me. I continued to struggle day to day.

Eventually, just over four years into my persistent pain journey, I received an episode of physiotherapy care that was less ‘routine’ and more ‘person-centred’. This episode of care was my turning point. The focus of this physiotherapist was much more on me as an individual, both in terms of my presenting physical symptoms and condition, and the person who I am that they manifest themselves within.

This physiotherapist subtly and sensitively empowered me and enabled me to become a more active and more equal partner in my healthcare. I felt he was genuinely interested in me as a person. He looked beyond my physical symptoms and he utilised his clinical judgement and problem solving capabilities in a way I didn’t feel others had before.

He taught me to listen to my body and to identify triggers to my pain. He helped me improve my physical function in a way no-one else had. He helped me understand that emotions and stress play a part in the experience of pain. He helped me understand about neuropathic pain, including ‘wind-up’ pain. He taught me just how complex the experience of pain can be, and he helped me develop ways to reduce my pain.

This episode of person-centred, evidence based, care was life changing for me. I have described it further *HERE*.

My Person Centred, Evidence Based Healthcare

It is clear to me now that I had desperately needed a more person-centred approach right from the start of my journey. From the day I entered accident and emergency, to the day of my discharge on the ward when the hospital doctor decided to make decisions about me without even seeing me, and then all the way through my patient journey.

I am convinced that if my care had been more person-centred that I could be in a very different place right now. Even if the permanent nerve damage couldn’t have been avoided, then I could have been helped to live well, and better manage my pain and condition right from the start. I am sure that I could have been spared a great deal of suffering, and also a lot of medical interventions.

I’m not a ‘typical’ patient, I’m not sure who is if I’m honest, and I don’t want to be viewed as part of a ‘cohort’ of patients with the same diagnostic label, eg prolapsed disc, sciatica or low back pain. There is no patient the same as me in the world, and there have been no research trials carried out on me. I have other co-morbid conditions, and my social, genetical, biological, psychological and other circumstances are unique to me. There is no research that can give an accurate prediction of my outcomes with any particular treatment option.

Although I do want research evidence to be utilised as part of the decision-making in my care, I need it to be considered in a realistic and balanced way. I need my narrative to be listened to, and for my individual presentation and circumstances to be centre stage. I need to be empowered to play my part in genuine shared decision-making. I need good person-centred, evidence based, healthcare.

Unfortunately, I will live in daily persistent pain, sometimes severe, for the rest of my life. It is with sadness that I say I don’t know whether some of this could have been avoided with better, earlier, more person centred, evidence based, healthcare.

Tina

@livingwellpain

www.livingwellpain.net

What an absolute gem of an article. I wish this could find its way into textbooks of all clinical specialties.

Gosh Mensah – thank you so much. That means more than I can say, especially as this was a fairly personal post, and different in many ways to my normal posts. Really grateful for this comment.