My persistent pain story began in the summer of 2008, and since then I have been treated by many clinicians within a system of Evidence Based Practice. Some of my healthcare has been excellent, and some much less so. Whilst thinking through and carefully considering these differences, I have found myself questioning some of the ‘concepts’ and ‘practice’ of Evidence Based Practice (EBP).

In this post I seek to explore the following areas relating to Evidence Based Practice:

- Communication, and information sharing, with the patient

- Shared decision making

- What constitutes evidence? The patient narrative

- ‘Routine’ health care and guidelines

- Sharing of information amongst clinicians

- Availability of relevant research evidence

I aim to explore these areas through my patient narrative, however perhaps unusually I have chosen to separate out my patient narrative into a second post, as I think my story is better read as an interrupted whole. My Evidence Based Practice patient journey can be read by clicking *HERE*. I would recommend reading my patient journey before reading the rest of this post, and then maybe reading again at the end. I hope my patient narrative will help put context to my thoughts on Evidence Based Practice.

What is Evidence Based Practice?

There is much debate about what Evidence Based Practice is and what it should be. One seemingly well respected ‘definition’ is:

‘Evidence-Based Practice (EBP) requires that decisions about health care are based on the best available, current, valid and relevant evidence. These decisions should be made by those receiving care, informed by the tacit and explicit knowledge of those providing care, within the context of available resources.’

(Dawes M, Summerskill W, Glasziou P et al 2005 Sicily statement on evidence-based practice BMC Medical Education 5 (1) 1-7)

There is a clear focus in this definition on the patient being the person who makes the health care decisions, informed by the clinician, with decisions based on good, valid and relevant evidence, and within available resources.

Reported difficulties with Evidence Based Practice

There have been a number of difficulties reported with the way evidence-based practice is implemented. For example, in 1995, Sir John Grimley Evans said:

‘There is a fear that in the absence of evidence clearly applicable to the case in the hand a clinician might be forced by guidelines to make use of evidence which is only doubtfully relevant, generated perhaps in a different grouping of patients in another country at some other time and using a similar but not identical treatment. This is evidence based medicine; it is to use evidence in the manner of the fabled drunkard who searched under the street lamp for his door key because that is where the light was, even though he had dropped the key somewhere else.’

(Evans JG. Evidence-based and evidence-biased medicine. Age Ageing. 1995; 24(6): 461-463)

And in 1998, Mark Tonelli commented:

‘… in EBM, the individuality of patients tends to be devalued, the focus of clinical practice is subtly shifted away from the care of individuals towards the care of populations, and the complex nature of sound clinical judgement is not fully appreciated.’

(Tonelli M. The philosophical limits of evidence-based medicine. Acad Med. 1999; 73; 1234-1240)

These reported difficulties echo some of my thoughts about the implementation of Evidence Based Practice, which I will now develop.

Shared decision making

It is fundamental to Evidence Based Practice that healthcare decisions should be made by the patients. Although I recognise that final decisions about my healthcare are mine, I would prefer to come to those decisions through a process of shared decision making. I want to have good two-way discussions with my clinician, within a good therapeutic alliance. I want to be sufficiently informed.

Much of my care has been paternalistic. Sometimes important decisions about my healthcare were made without me even being consulted or involved at all. At other times I was expected to make important decisions, sometimes with potentially life-changing consequences, without being given even the barest of information. I was denied the right to make well informed and ‘good’ decisions. I was not valued as an equal partner in shared decision making. It feels as though sometimes I was not valued at all.

I believe good shared decision making, within a good therapeutic alliance, is an important element of Evidence Based Practice.

Communication, and information sharing, with the patient

Evidence Based Practice is built on the premise that I, as a patient, should be able to make properly informed decisions. Without at least adequate communication, and at least adequate sharing of information, this is impossible to do. Communicating appropriately and well is a skill. Good communication is fundamental to providing good care.

Communication, including sharing of information, is a two-way process. The clinician must communicate in a way that the patient understands and must share information at an appropriate level. The clinician also has a responsibility to facilitate good communication from the patient, and to facilitate the patient sharing their information with the clinician. They must empower the patient. They must listen.

Sharing of information amongst clinicians

Clearly decisions about healthcare should not be made in isolation. Sadly, I believe the lack of coordination of my care, and the lack of sharing of information between clinicians were significant factors in the failings of my care.

Although I appreciate the difficulties encountered with data protection regulations, and the sharing of patient data across different hospital and clinician computer systems, and of course shortage of clinical time, I’m sure there must be ways to better co-ordinate a patients care than I experienced.

I believe good sharing of information amongst clinicians, and good coordination of care, to be vital components of Evidence Based Practice.

‘Routine’ health care and guidelines

I understand that recommendations for ‘routine’ treatment can come out of research trials and that these ‘routine’ treatments will have been ‘proven’ to work for many people. However, the research studies will also have shown that they don’t work for every individual, and the research studies will have been based on a cohort of people who cannot possibly be fully representative of me. I am unique. I am an individual.

I completely understand the need for, and benefit of, guidelines based on research, such as NICE guidelines, but surely that is all they are, guidelines. They are not meant to dictate care in all circumstances, and for every individual.

It seems to me that I was often treated as one of a cohort of patients, with the expectation that ‘routine’ treatments would work for me. I found that even when it must have been crystal clear that these treatments weren’t working well enough for me, or that I needed more practical and functional help, so these treatments continued.

Surely it must be important to maintain the focus on the individual receiving care, and before implementing a ‘routine’ treatment, or simply following a guideline, to consider whether other options might be better indicated for that person?

I acknowledge the system wide drivers that require clinicians to follow guidelines, for example commissioners, policy, normative practice etc, but surely there must be a way to deliver more personalised care?

What constitutes evidence? The patient narrative

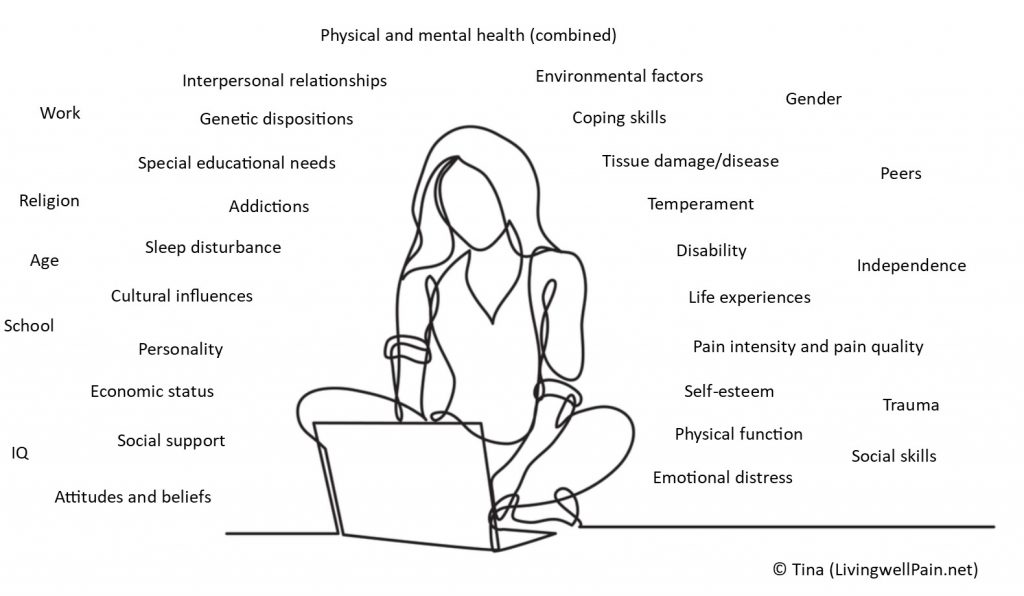

In Evidence Based Practice, at least as important as research evidence, if not more important, must surely be the patient’s own narrative? Their story. Their experiences, their genetics, their symptoms, their life. Everything about them that is needed to make sound healthcare decisions.

I suspect, but I can’t know for sure, that evidence from ‘research’, and guidelines carried proportionately too much weight in some decisions made by my clinicians. At least that’s the way it seems to me. I don’t think my patient narrative, individual presentation and circumstances played proportionately enough of a role, or sometimes even at all.

My best healthcare occurred when I was treated within a strong, more person-centred model of Evidence Based Practice, and my patient story was listened to. I am sure that research evidence was considered but good clinical judgement, genuine curiousness, patient empowerment and a particular focus on me as an individual occurred.

I believe listening to the patient narrative is key to good healthcare and to good shared decision making. ‘Evidence’ in Evidence Based Practice means more than just research evidence.

Availability of relevant research evidence

My understanding, which may of course be wrong, is that research evidence is sometimes seen as the most important element of Evidence Based Practice. Although I understand why this might have come about, it concerns me deeply that research evidence may play too great a role in my healthcare.

After all, I am aware that not all clinicians properly understand, or are aware of, the evidence that is available. I am aware that there can be two pieces of research evidence that effectively give opposing results. I am aware that clinicians do not always have the time available to keep abreast of evidence. I am aware that not all clinicians thoroughly read a research report, maybe reading only the abstract and the conclusion. I am aware that there is much research yet to be done. I am aware that not all research is carried out rigorously.

Most importantly though, I am aware that I would almost certainly be excluded from any research being undertaken on my primary condition of sciatica, maybe because I have had back surgery or maybe for some other reason. There is no research anywhere in the world that can possibly give a fully reliable predictor of my success with any particular treatment. They may well be able to give some indications, but that is all.

Although research evidence is an important element in my care, I don’t want it to be viewed as the most important element, trumping all others. It is one tool in the clinician/patient’s toolbox.

Final thoughts

In summary, looking forward I hope that my Evidence Based Healthcare will:

- be truly person-centred and empowering

- include my narrative as a vital and important piece of ‘evidence’

- involve proper coordination of my care

- be reflective, with clinicians looking back at treatments that did and didn’t work for me, and properly taking this information into account

- involve shared decision making, occurring within good therapeutic alliances

- provide me with sufficient, well balanced, information in order for me to make good final decisions

- be informed by up to date and relevant research and by guidelines, but not dictated by them

- have a focus on function and independence

- provide me with understanding of my condition, and also transferable skills, so that I can build on my therapy care and manage my condition beyond the clinic door

As always I am very interested and happy to hear other’s thoughts on this.

Tina

@livingwellpain

www.livingwellpain.net