I have been told I have sciatica, but what does this mean? What is sciatica? What is radicular pain and radiculopathy? What is neuropathy? How do these terms fit together? What happened in my body to cause my condition? How might back surgery help?

Ten years ago, I experienced a manual handling accident which resulted in me being diagnosed with ‘disabling right sided sciatica’. My L5/S1 lumbar disc herniated and compressed my S1 nerve root. Since that time, I have had many clinicians involved in my care, many of whom have provided me with an explanation of my condition. I have also read books about my condition and articles on the Internet. Overall, I have received a great deal of information about my condition, but some of it has been conflicting, some of it beyond my scientific/medical knowledge, some of it too simplistic, and some of it just plain inaccurate.

It feels as though I have a lot of jigsaw pieces representing different pieces of information about my condition, but I haven’t yet been able to put them together to form a complete picture. Currently all the individual jigsaw pieces are blurry and I hope, through this blog, previous blogs and future blogs, to explore these jigsaw pieces, clarify and clean them up, fit them together, and finally better understand my condition.

The initial set of jigsaw pieces I want to clean up, and then fit together, are:

- The anatomy involved in sciatica

- What is radicular pain?

- What is radiculopathy?

- What is radicular syndrome?

- What is sciatica?

- What does sciatica feel like?

- What causes sciatica, radicular pain and radiculopathy?

- Common back surgery for sciatica

Please note that understanding ‘sciatica’ as described in this blog is only one element of understanding my overall persistent pain condition. There are many other elements involved. I have written about my overall understanding of my pain condition in a blog called ‘A patient’s understanding of persistent pain’ which can be accessed HERE. In addition there are some other elements of my pain experience I am yet to explore, for example Central Sensitisation.

First a huge and important disclaimer. I am not in any way medically qualified, and do not pretend to be. Everything I say is from a viewpoint of a person with 10 years-worth of sciatica suffering. I have tried to write accurately but I cannot guarantee I have got everything right. I’m very happy for physiotherapists, or other clinicians, to put me right on anything!

1. The anatomy involved in sciatica

The human body is hugely complex. It comprises a skeleton, a nervous system, organs, skin, a circulatory system and many other parts.

It is the skeleton and the nervous system I need to focus on in order to aid my understanding of sciatica.

The spine

An adult human body has 206 bones, connected with a network of tendons, ligaments and cartilage. The bones fit together to form the skeleton, as shown below.

The following diagram shows nicely the backbone, or spine, within a human body.

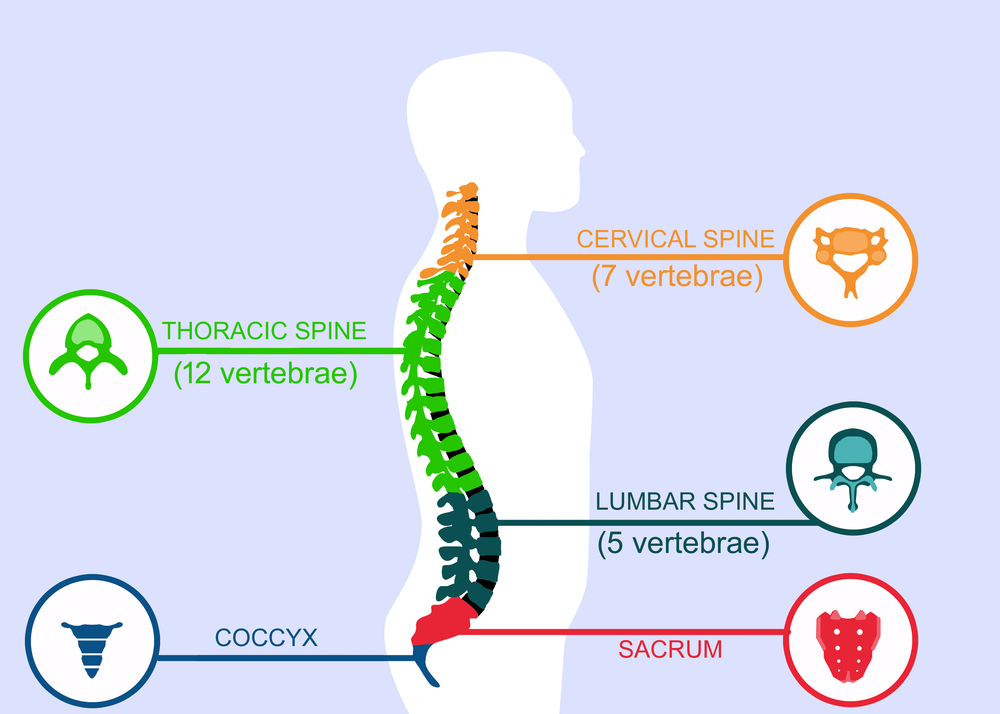

The spine is thought of as having three main parts, the cervical spine, the thoracic spine and the lumbar spine, as shown below. At the bottom of the spine is the sacrum, and below that the coccyx or tailbone. It is the lumbar spine and the sacrum that are involved in sciatica.

The bones of the cervical and thoracic spine serve to protect the main spinal cord, which is the central, and apart from the brain, probably the most important part of the body’s nervous system. The bones of the lumbar spine protect the main nerves which serve the lower part of the body.

The spine is made up of bony vertebrae, which link together to form a strong moveable structure. Between each vertebra is a disc (shown below), which acts as cushioning and facilitates movement of the spine.

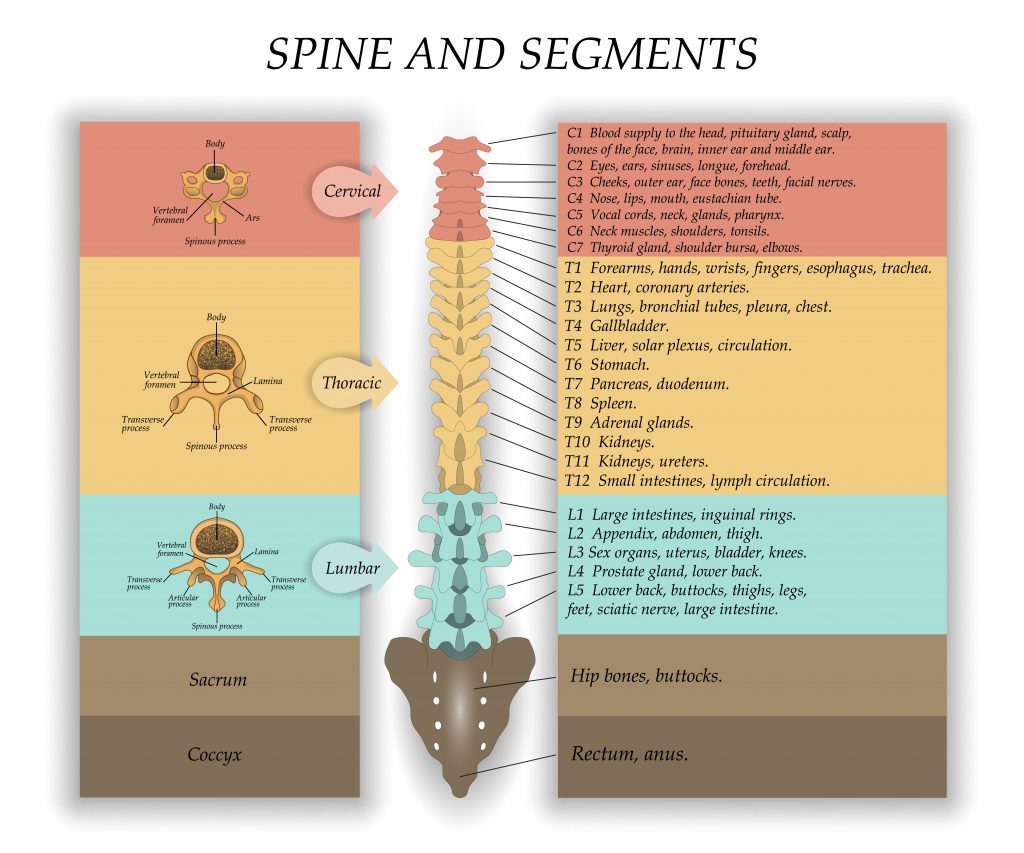

Each vertebra of the spine is given a number, as shown in the diagram below. The relevant section for sciatica difficulties is the lumbar spine, which is L1 to L5, and the sacrum. The sacrum is the bony part at the bottom of the spine, and is composed of five fused bones, of which the top bone is called S1. On the left of this diagram you can see cross sections of the vertebra. It is important to note the different shapes of the verterbra cross sections in the different spinal sections. This might help when looking at other pictures online to work out whether you are looking at the relevant section of the spine or not. This has caught me out more than once!

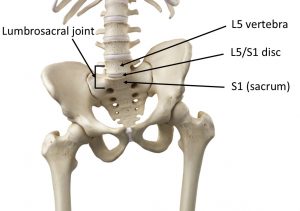

The following picture shows in more detail how the lumbar spine fits onto the sacrum. You can see that the bottom disc lies between the vertebrae called L5 and the sacrum bone S1. The L5-S1 junction is a common area for symptoms to arise from. It is thought this may be because a significant amount of load goes through this region. This L5-S1 segment is called the lumbosacral joint. It is a problem with the disc at this lumbrosacral joint that has caused my difficulties.

The nervous system

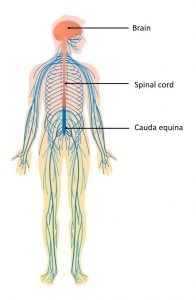

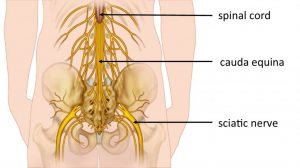

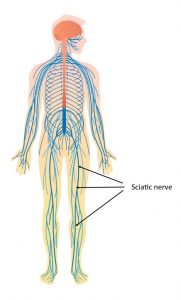

The nervous system, shown below, consists of the central nervous system (the brain, spinal cord and the nerves forming the cauda equina) and the peripheral nervous system (nerves and ganglia outside of the brain, spinal cord and cauda equina). It is basically the body’s ‘electrical wiring’.

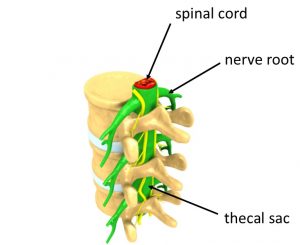

It is important to note in the diagram above that the brain and spinal cord are coloured in orange and the nerves and ganglia in shades of blue. Before attempting to clean up this jigsaw piece I had erroneously assumed that the spinal cord goes all the way down to the bottom of the spine, but it doesn’t, it ends at the level of vertebrae L1-L2. After the spinal cord terminates, the central nervous system continues as a bundle of nerves called the cauda equina. The spinal cord is housed in a protective sac, called the thecal sac (often known as the dural sac), and this sac continues down to S2 in order to protect the nerves of the cauda equina.

The nerves of the cauda equina serve the lower half of the body, and branch out from underneath the spinal cord like a ‘horse tail’. The latin name for ‘horse tail’ is cauda equina, hence it’s name.

On the diagram above you will see a dark blue section underneath the spinal cord, which is the continuation of the thecal sac. This dark blue section of the thecal sac is the protective housing for the nerves which comprise the cauda equina, and contains the same fluid that bathes the spinal cord, the cerebro spinal fluid. The cauda equina is made up of paired nerve roots (sensory and motor), which are bundled together in one nerve root sheath. Sensory nerves gather information about the environment (eg touch, temperature) and send it to the brain, and motor nerves tell muscles to contract, thereby making you move. You will see that the nerves exit the thecal sac at different levels. At each level there is a pair of nerve roots contained in one sheath exiting left, and another pair of nerve roots contained in one sheath exiting right.

The diagram below shows quite nicely where the spinal cord ends and where the ‘horse tail’, or cauda equina, of nerves start. Unfortunately, the diagram doesn’t show the thecal sac that contains the horse tail of nerves.

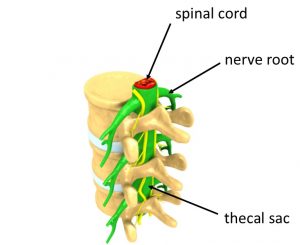

The following is a diagram of a thoracic vertebra, rather than a lumbar one that we are particularly interested in, but it does show quite nicely how the spinal cord, inside the thecal sac, is housed in the vertebra. It also shows nerves exiting between two vertebral segments, at the same level as a disc. When a nerve exits the thecal sac it is called a nerve root.

Nerve roots exiting the thecal sac between two vertebral segments are given the name of the segment above it. For example the nerve root that exits the thecal sac between lumbar segment L4 and lumbar segment L5 is called the L4 nerve root (L4 is above L5), and the nerve root that exits between the L5 and sacrum segment S1 is called the L5 nerve root.

The sciatic nerve

The nerve roots that emerge from the sacrum include S1, S2 and S3. The 5 nerve roots L4, L5, S1, S2 and S3 join together to form one long nerve, the sciatic nerve. This nerve then travels down the back of each leg, branching out to provide motor and sensory functions to specific regions of the leg and foot.

You can see in the following picture how the five nerve roots join together to form the sciatic nerve (depicted in red).

The sciatic nerve runs from the lower back through the hips and buttocks and divides into other portions around the knee and continues to the feet. The sciatic nerve is the largest nerve in the body.

If we look again at the diagram below, which shows the nerves in the body, the sciatic nerve is the long dark blue nerve arising from the back, from the 5 nerve roots, and traveling all the way down the leg and into the foot.

2. What is radicular pain?

Radicular pain is pain arising from the irritation of a nerve root. This may be a sciatic nerve root, or could be a nerve root in another part of the body.

Many people think of radicular pain as ‘radiating’ from the nerve root down the associated nerve, but in my experience, and that of others, this is not a good description of radicular pain. For example, my sciatic pain is caused by the irritation of one of my sciatic nerve roots (S1), but I often experience pain in only the lower leg, or only the buttocks, or only the upper thigh, or only the foot, or sometimes a combination of these. I do occasionally experience pain that literally radiates straight down my sciatic nerve, but that may not be the norm.

Radicular pain can take multiple forms. Sometimes it can be felt of as sharp shooting pains and sometimes as a burning sensation. It can have an ‘electric’ type quality, and can sometimes feel like an electric shock.

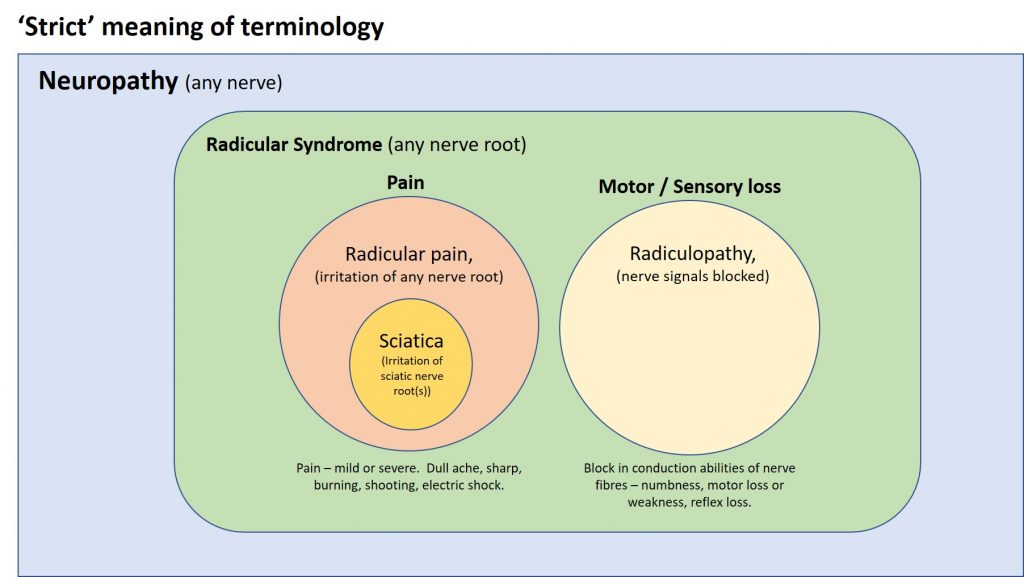

Radicular pain can be thought of as a subset of neuropathic pain. Neuropathic pain refers to pain related to any nerve in the body (including nerve roots), whilst radicular pain refers to pain specifically related to a nerve root. Sciatic pain is a subset of radicular pain (and therefore neuropathic pain) as it refers to pain related to one, or more, of the sciatic nerve roots.

3. What is radiculopathy?

When a nerve root is compressed or damaged then you may experience sensation changes, such as numbness, weakened reflexes and motor loss. This is called radiculopathy. Radiculopathy occurs because some of the nerve signals are blocked from travelling through the nerve.

The numbness is distributed roughly along the path of the nerve (along the relevant dermatome) and any motor weakness will relate to the group of muscles that the relevant nerve serves.

Although radiculopathy and radicular pain commonly occur together, radiculopathy can occur in the absence of pain, and radicular pain can occur in the absence of radiculopathy.

It should be noted that some people refer to radiculopathy as including radicular pain. I don’t think this is strictly correct, but is quite common.

The nerve root affected in radiculopathy may be the sciatic nerve root, but like radicular pain, it could be a different nerve root in the body.

Radiculopathy can be thought of as a subset of neuropathy. Neuropathy refers to the symptoms occuring because some of the nerve signals are blocked, but this could be for any nerve in the body (including any nerve root). Radiculopathy specifically refers to a nerve root.

In the same way that radiculopathy is commonly used to encompass both the pain and the changes in sensor/motor control arising from a nerve root, neuropathy is often used to encompass similar symptoms, but for any nerve in the body (including any nerve root).

4. What is radicular syndrome?

When you have radicular pain combined with radiculopathy (from the same nerve root) then you might be diagnosed with radicular syndrome, however I don’t think this terminology is commonly used in practice.

Some people get radicular syndrome in their arms, arising from irritation of a nerve root in their neck, others may experience symptoms in their legs, arising from irritation of a nerve root in their back.

Radicular syndrome can be thought of as a subset of neuropathy (neuropathy refers to any nerve in the body, including nerve roots, whilst radicular syndrome is focused on nerve roots).

5. What is sciatica?

I have discovered whilst trying to clean up this jigsaw piece that there is no commonly agreed ‘definition’ or shared understanding of the term ‘sciatica’. Different clinicians have different views, and the information available to the public on the Internet, or within books, reflects that lack of consensus.

There also seems to be debate about whether sciatica is a symptom of another condition or a diagnosis in it’s own right.

I have decided to look at ‘What is sciatica’ in two different ways. First of all I have looked at what a ‘strict’ definition of sciatica might be, and then secondly I have taken a pragmatic view of how I think the rheumatologist who gave me my diagnosis of sciatica considered my condition to be, and how I think my condition pragmatically fits into an overall ‘concept’ of ‘sciatica’.

Strict definition of sciatica

My understanding is that in strict and simple terms, sciatica is the name given to pain caused by irritation of one or more of the sciatic nerve roots in the lower back. Pain might be felt anywhere along and around the path of the sciatic nerve, even though the actual irritation is at the site of one of the sciatic nerve roots in the lower back. Sciatica may be associated with neurological dysfunction, such as weakness and numbness, but strictly speaking the term sciatica only describes the pain element.

Strictly speaking I understand sciatica is a symptom rather than a specific condition, illness or disease.

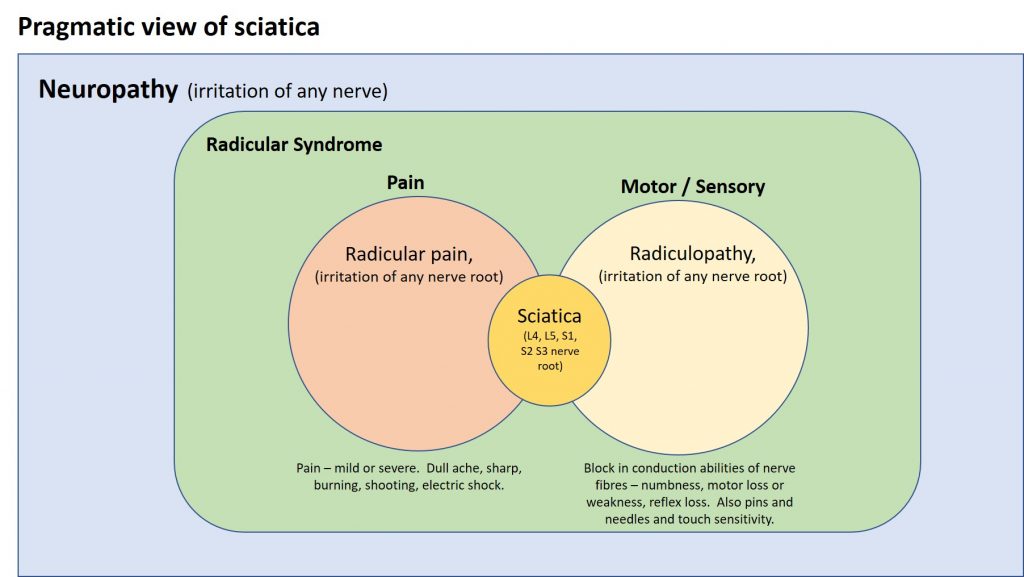

Whilst trying to get to grips with this part of the jigsaw, I created a Venn diagram, shown below, which I think illustrates how this strict definition of sciatica fits in with the concepts of radicular pain, radiculopathy, radicular syndrome and neuropathy. Fundamentally, in the strictest sense, sciatica is a subset of radicular pain, as radicular pain is pain produced from the irritation of a nerve root, and sciatica is the pain produced by one or more of 5 nerve roots, the sciatic nerve roots. (I understand there is some debate as to which nerve roots contribute to sciatic pain, but this is beyond the scope of this post). Strictly speaking sciatica is only pain though, and any associated neurological deficits (radiculopathy) are separate to that, as indicated in the diagram.

A pragmatic view of sciatica

Many clinicians and Internet articles refer to sciatica as including both the pain element and the neurological deficits such as numbness, reflex loss and motor weakness.

I’m aware that the rheumatologist who diagnosed me with sciatica knew that I experienced numbness and reflex loss, and I am certain that her use of the term ‘sciatica’ was intended to encompass both the radicular pain I was suffering and the radiculopathy (numbness and reflex loss).

I’m not a clinician and so I can’t argue out whether this is correct or not, but as a patient I can accept that if I take a pragmatic view of the differing views about the terminology of sciatica, and allow myself to move away from the strict definition of sciatica, that an understanding of sciatica as encompassing the two elements, radicular pain and radiculopathy, works for my situation, and me. Both the radicular pain and radiculopathy in my case are centred on the S1 root nerve, and the two together explain my diagnosis of sciatica.

A revised Venn diagram for this situation is below:

I will use this pragmatic description of sciatica from now on.

6. What does sciatica feel like?

Some people experience only pain as part of their sciatica, whilst others experience only motor/sensory changes, and others unfortunately experience both. Some experience relatively mild symptoms, whilst others have symptoms that are fundamentally disabling.

Sciatic pain can be mild or severe, ranging from a dull ache to pain that is described as sharp, burning or shooting. It can be excruciating and sometimes it can feel like a jolt or electric shock. The path of the pain follows roughly the path of the sciatic nerve, which runs from your lower spine to your buttock and down the back of your thigh and calf and into your foot. At any one point in time you may experience, for example, pain in your calf and not your thigh, at another point pain right along the sciatic nerve pathway, and at another point pain in your buttocks. At other times you may experience a combination of these. Sciatic pain can be highly variable, and affects people in different ways.

As well as pain you may experience sensory/motor loss symptoms, such as numbness, reduced reflexes and motor weakness.

The areas you may experience sciatic symptoms are different depending on which nerve root is compressed:

- If the L4 nerve root is affected then pain, numbness or tingling may be felt in the thigh. Weakness may include the inability to bring the foot upwards (heel walk). You may have reduced knee jerk reflex.

- If the L5 nerve root is affected then symptoms may extend down to the big toe and ankle. You may have weakness in moving your big toe and potentially weakness in your ankle (called foot drop).

- If the S1 nerve root is affected then symptoms may extend to the outer part of the foot, and may radiate to the little toe or toes. Weakness may include difficulty raising the heel off the ground or difficulty walking on tip toes. You may have a reduced ankle-jerk reflex.

If more than one nerve root is compromised, then you may experience a combination of the above symptoms.

Even if there is only one nerve root compromised you may experience a combination of symptoms, in fact this is quite common. This is thought to be due to the inflammation surrounding the irritated nerve root spreading to neighbouring nerve roots. Every instance of sciatica is unique.

Sciatica can be constant or intermittent. It can vary according to your activity. Prolonged sitting or standing can aggravate symptoms, and some people find pain can be worse when you cough or sneeze. It may be exaggerated by physical activity. Usually only one side of your body is affected.

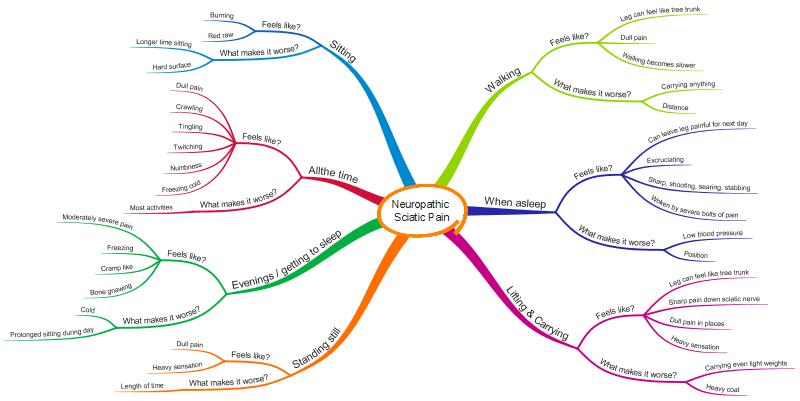

The following diagram illustrates how I am affected by sciatica. Unfortunately, you can’t tell from the MindMap how much pain I have, or how often I get each of the symptoms. I can’t yet think of an easy way to do this. I should also add that most people don’t suffer the range of symptoms or the severity of symptoms that I do. There really is a wide range, from very low level symptoms to more severe symptoms than I have.

7. What causes sciatica, radicular pain and radiculopathy?”

In simple terms, sciatic pain and other sciatica symptoms are caused by one of the sciatic nerve roots becoming both compressed and inflamed. Common causes for this are:

- Herniated disc

- Degenerative disc disease

- Isthmic spondylolisthesis

- Spinal stenosis.

My condition was primarily caused by a herniated disc and so that is the cause I will consider here.

A herniated disc is the most common cause of sciatica, radicular pain and radiculopathy.

Looking again at the diagram showing the spinal cord and the nerve roots in the thoracic part of the spine, you can see that the discs between the vertebrae are right next to the thecal sac (green column going down the middle of the picture housing the spinal cord) and the nerve roots. This is also the case for the discs in the lumbar spine, with the exception that in the area of the lumbar spine we are interested in the thecal sac houses the cauda equina nerves and not the spinal cord.

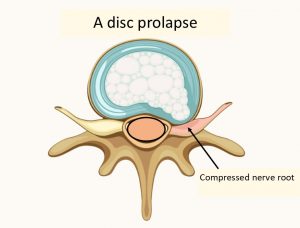

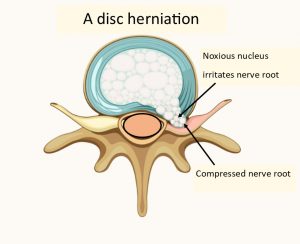

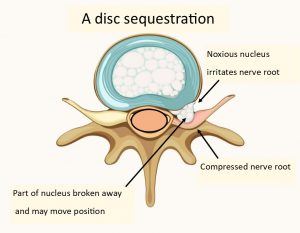

The following series of diagrams will show how a disc prolapse (protrusion), disc herniation (extrusion) and disc sequestration affects the exiting nerve roots. The diagrams are of a cross section across the vertebra and disc, and show only the exiting nerve root (this is for simplicity and understandability reasons).

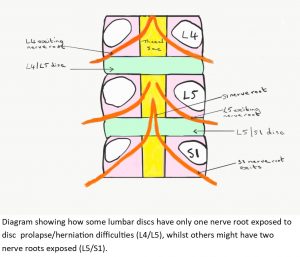

It should be noted that at some levels of the lumbar spine, in particular at L5/S1, there may be another nerve root that has also left the thecal sac, and which therefore may also be affected by a disc prolapse, herniation or sequestration. For example at L5/S1 the L5 nerve root will have left the thecal sac and be exiting at that level, but the S1 nerve root may also have left the thecal sac and be travelling down past the L5/S1 disc ready to exit out of S1/S2. It is difficult to show this second nerve root on these cross sectional diagrams due to their direction of travel, and so I will attempt to illustrate this scenario later on.

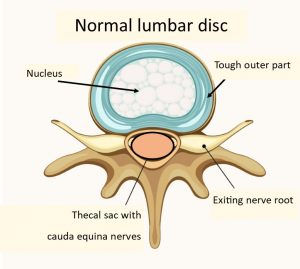

The following diagram shows a cross section of a normal lumbar vertebra and spinal disc. The spinal canal houses the thecal sac, which houses the cauda equina of nerves. The parts that look a little like bull horns, are the exiting nerve roots.

In simple terms the disc is composed of two parts, a tough outer part and a softer inner part (called the nucleus).

Disc prolapse or protrusion

Unfortunately, sometimes a disc becomes degenerative or is injured and the nucleus of the disc starts to protrude through the outer layer and pushes on the nerve root, as shown below. This compression of the nerve root may or may not be enough to cause sciatica symptoms. This varies from person to person.

Unfortunately many people refer to a disc prolapse, or prolapsed disc, as a ‘slipped disc’, but this isn’t helpful terminology as the disc doesn’t move or slip, it actually changes shape as shown below.

Disc herniation or extrusion

If the nucleus breaks through the outer part and leaks out then this is called disc herniation, or extrusion. The contents of the nucleus is extremely noxious and will inflame the nerve root it leaks onto. Both the compression of the nerve and the noxious substance leaked onto it may cause sciatica symptoms.

Disc sequestration

Sometimes part of the nucleus breaks away and disc sequestration occurs. This happened in my case.

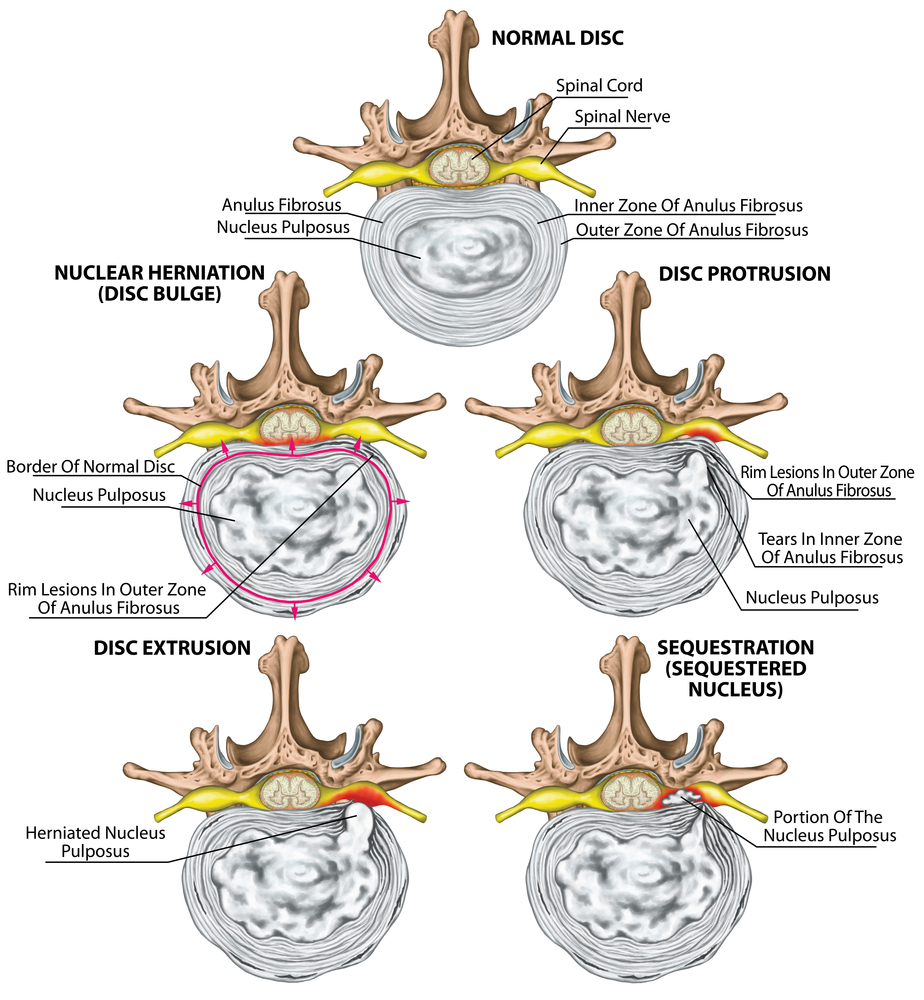

The following diagram looks in a little more detail at the processes involved. You will see that the diagram is labelled showing the spinal cord, and so strictly speaking this must be showing vertebra at the level of L1/L2 as that is where the spinal cord ends. Lower down the lumbar spine the area marked in the diagram as spinal cord would be the thecal sac containing the nerves forming the cauda equina.

Finding accurate pictures I can use for this blog has been difficult, but perhaps the following diagram helps to illustrate how confusing the information in the public domain can be. I’m sure I could be forgiven following looking at this diagram for thinking that the spinal cord runs through all the lumbar vertebrae. Why wouldn’t I think that! Nevertheless, the diagram does show a useful summary of the stages of disc herniation, and also serves the purpose of illustrating how confusing much of the information in the public domain can be. I think it’s important to bear this in mind when seeking information, particularly from the Internet, about sciatica.

Whilst cleaning up this jigsaw piece I discovered I had another major misunderstanding. I knew that the vertebral segment affected for me was my L5/S1 segment, and I also knew that it was my S1 nerve root that had been damaged. As already explained the exiting nerve root takes the name of the vertebra above it in the lumbar region, and so the exiting nerve root for L5/S1 is the L5 nerve root, and not the S1 nerve root. This caused me great confusion, but it did lead me to discover that as well as the exiting nerve root being exposed to the disc (outside of the thecal sac) there could be another nerve root that has exited the thecal sac in advance of the lumbar segment that it will exit.

For example at L5/S1 it is common to find that as well as the L5 nerve root being exposed to a prolapsing/herniating disc, the S1 nerve root is as well. The S1 root doesn’t exit at the L5/S1 segment, but is there ready to exit out of the sacrum (S1/S2). I’m not sure people know why this happens, but I understand for many people it does. This means that when the L5/S1 disc prolapses, herniates, sequestrates etc there are two nerve roots it might impact on, the L5 and S1 nerve root, not just the exiting nerve root (the L5 root). There is the potential for both nerve roots to be affected by the prolapse/herniation, or just one. This works in a similar way at other levels, although the possibility of having two nerve roots exposed to a disc is greater at the L5/S1 level. In my case the disc herniated in such a way that my S1 nerve root was mainly affected.

I don’t think it is easy to illustrate the situation whereby a second nerve root is exposed to a prolapsing disc, but I hope the following diagram may give some idea. In this diagram the lumbar segments are on top of one another, with the discs in between.

I had an MRI scan which revealed my herniated disc. Interestingly I have discovered that it is not uncommon for an MRI to show a prolapsed, or even herniated disc, with the person concerned having no symptoms whatsoever. MRI’s commonly show degenerative back changes. This is entirely normal, especially for the slightly older population. There is often nothing to worry about at all.

I’ve also discovered that sometimes a radiologists report for an MRI shows only a small disc protrusion, but the person concerned is suffering severe symptoms. This was the case for me.

MRI results of a back are not always a good predictor of how a person may be affected.

I have had numerous MRI scans, and my experience is that it is important not to get over-concerned with the results of an MRI report on a back, but to discuss the results with your clinician. A radiologist report can sometimes be a frightening thing for a patient to read, but as I learnt a lot of the degenerative changes in your back which are shown up on an MRI, and being written about in a radiologist’s report, are entirely normal. This has been another important learning point for me.

8. Common back surgery for sciatica

Surgery to relieve sciatica is usually considered only after an extended period of non-surgical (conservative) treatment has not proved successful enough.

Depending on the cause and duration of the sciatic pain, one of two general surgeries will typically be considered:

- a microdiscectomy (or discectomy)

- a lumbar laminectomy.

The main idea behind surgery is to relieve the nerve root irritation or compression.

During a discectomy the surgeon will remove the portion of the disc that is herniated and pressing on the nerve root.

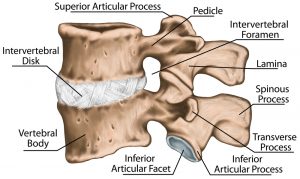

During a laminectomy the surgeon will create space for the nerve root by removing the lamina, which is the back part of the vertebra that covers the spinal canal. The diagram below shows the invertebral foramen which is basically the hole that the nerve root passes through, and the lamina that sits just behind it. Removing part of the lamina provides a larger hole for the nerve root to pass through, so helping to reduce any compression occurring on the nerve root.

There is good evidence that discectomy is effective in the short term. but, in the long term that it is no more effective than prolonged conservative treatment.

I underwent combined discectomy and laminectomy surgery 18 months after my accident which relieved the pressure on my S1 nerve, however it appears that my nerve had been permanently damaged by then and I have been left with residual symptoms. I know of people who have had much better responses to surgery.

Completing the jigsaw

So there we have it, I hope I have cleaned up the jigsaw pieces I set out to and fitted them together to get a clearer picture of my physical condition. It’s been quite a journey of exploration for me.

Before embarking on this task I hadn’t appreciated quite how many bits of basic understanding about anatomy, sciatica, radicular pain, radiculopathy and neuropathy I didn’t understand, and how much I had just plain misunderstood.

Although this post was written predominantly to aid my own understanding, I hope this exploration of my jigsaw pieces might also be useful to others. I plan to explore some of these basic concepts in further detail in future blog posts.

I would like to acknowledge the support given to me by Matt Low (@MattLowPT), David Poulter (@Retlouping), Adam Dobson (@adamdobson123) and Tom Jesson (@thomas_jesson). They have all helped me gain a better understanding of sciatica, radicular pain, radiculopathy, neuropathy and the anatomy involved, and have supported me with this post.

Tina

@livingwellpain

www.livingwellpain.net

Thanks for a great description of sciatica. I have ongoing neuropathic pain from a disc herniation that compressed my L2 nerve. So its not sciatica because the L2 does not involve the sciatic nerve. My herniation was a far lateral one which is fairly uncommon, particularly at the upper lumbar levels. With these type of herniations the top exiting nerve root is compressed and in particular the dorsal root ganglion which is located in the foramen. So it was my L2/3 disc that herniated and compressed the L 2 nerve. With the more common types of herniations it would have been the L3 nerve that was compressed. Far lateral herniations are much more painful than others because the dorsal root ganglion is the main part of the nerve that receives the pain signals. These herniations have a very small window of opportunity for surgery to relieve the pain and prevent ongoing neuropathic pain (approx 12 weeks) Mine was compressed for 9 months unfortunately. Like you, I did my research after I became a “chronic pain patient”. Sorry about the essay but I wanted to share my knowledge so people with far lateral disc herniations are made aware of the risks of delaying surgery.

How interesting – thank you. Sorry that you also live with chronic pain though! Yes, hopefully your response may help others. Interesting about the 12 week window of opportunity. Thank you….. Tina

Great article you explain it much better than professionals x

Thank you Kate – I really appreciate that. It took me a long time to write, but it was worth it in terms of improving my own understanding, and also hopefully that of others.

Where does an antalgic posture, without radicular symptoms or radiculopathy fit within this picture. My understanding is consider this a disc injury without nerve root compression and proceed with caution.

This is great information, and very well written.

I’m going through similar issues although seemingly not as serious as yourself.

Just reading this has really helped me understand whats going on in the lower back. I’ve struggled with electric shock type pains for around 6 years, had 2 MRI’s which revealed bulging discs, but i never get any pains in my legs and for that reason i hear the words “wear and tear” quite a lot from various medical professionals, but as you know it can be a lot worse than that makes it sound.

I was directed to this post by my physio and i can see why she recommended it to me, very informative.

Thanks for sharing and good luck for the future

Andy

Thank you Andy – I really appreciate your comments, and really pleased the post was helpful. Yes, I’ve heard a lot about ‘wear and tear’ too, I guess in some ways it’s a helpful phrase, but in other ways it just isn’t. Wishing you good luck for the future also 🙂

Tina

Thank you for the detailed write up. It was much more informative than some of the other online articles I have found and read. I had a laminectomy and distectomy on nov 4 of this yr. My L5/S1

Disk was herniated some time ago and was compressing against my s1 nerve. In addition I had spinal stenosis that was reducing the spinal canal. My surgery went well. It has reduced the sciatic pain I was feeling down my right leg. But I do have some numbness in my rear and will have some numbness in my right foot when I walk for an distance like half a mile or beyond. I am wondering whether if i have permanent nerve damage from not getting surgery sooner.

Are your symptoms getting any better over time? Just wondering if I this numbness will improve or whether it is permanent. My doctor says it may take 3-6 months or longer to tell.

Thanks

Richie

Thank you Tina! Awesome descriptions, information & images! Yes – totally agree – better than professional spine medical groups. In 2015, I had a L5 discectomy lasted 6 years. I’ve been since 1am & pinched the same root nerve again – same way as the first time, turning over in bed while asleep. I just saw the medical group yesterday since 2015 episode, this time for a knee injection & back X-ray only cause I mentioned last minute. Incredibly, been having leg foot & back symptoms for months but did not recognize them leading to another pinched nerve. Whatta dummy, I can be! Suns coming up, thank you for doing Gods work!!

It is helpful to have more understanding related to the lumbar and the many possible negative impacts that discs/nerve roots can have, albeit depressing that the pain caused may be somewhat unmanageable.

I have had L5 herniated disk pain off/on for 15 years but the pain was not severe and would usually subside after awhile. However, in the last year the pain had become so severe that just sitting at my desk at work was unbearable. I purchased an adjustable desk riser (but standing too long is not a cake walk either) and was prompted to get a MRI. It was quite shocking to learn that the reason why the pain was not subsiding was due to multiple herniations and bulging from L1 all the way to S1. So, where does one go from here? I am glad to say that I have just started with a spine pain management practice which utilizes numerous treatments, including nerve block/injections, chiro rehab, physical therapy as well as medications. I feel hopeful that my pain can be managed. Meanwhile as I am getting ready to retire in a few short months I feel that having more flexibility as to when I sit, stand or walk, gives me additional hope about being able to manage my pain better going forward. I hope that sharing my personal pain situation helps to give some hope to some who may feel their pain is also unmanageable. Better days are ahead so don’t lose hope.

Thank you for your post.

Thank you for sharing your journey Anna, I am sure it will be helpful to others. 🙂

Wishing you all the best

Tina